Patrice E. Jones likes to say her household bought its 40 acres — the quantity of land promised, then denied, to previously enslaved folks within the U.S. authorities’s solely actual try at reparations for hundreds of years of treating Black folks as property.

It was her ancestors’ stretch of farmland in rural Hazlehurst, Miss., bought by her great-great-grandparents within the Eighties, that helped carry a household born into slavery up from extra humble cotton-farming beginnings to school and trade-school schooling inside a era.

Jones’s great-grandfather, Rev. William Talbot Helpful, born on the forested property solely three many years after the top of the Civil Warfare, even joined the Tuskegee Quartet and sang at Booker T. Washington’s funeral, Jones mentioned. That was whereas Helpful was paying his manner by means of the Tuskegee Institute, the college Washington based, with the labor and expertise he’d earned from working the land in Copiah County, Miss., the place greater than half of the inhabitants had been enslaved in 1860, Jones mentioned.

His personal youngsters, raised in New Orleans, included Dr. Geneva Helpful Southall, the primary girl to get a doctorate diploma in piano efficiency, and D. Antoinette Helpful, a flutist who — after learning on the New England Conservatory of Music, the Northwestern College Faculty of Music and the Paris Conservatoire — joined the Richmond Symphony and directed the Nationwide Endowment for the Arts’ music program. Their siblings, youngsters and grandchildren turned activists, tradespeople, lecturers and artists.

That’s a credit score to the facility of landownership, Jones mentioned. It’s why she’s reclaiming the property her household deserted many years in the past in an effort to return it to its former glory and to indicate what Black households might need had — and will nonetheless.

“I don’t suppose I’d be alive, had we not had that land to set foot on proper out of slavery,” Jones, a 35-year-old influencer, content material creator and educator on the College of New Orleans, instructed MarketWatch. “My ancestors who bought the land at first had been each born enslaved folks, and so they had been in a position to make use of that land to farm cotton, have many youngsters, assist themselves, and take a look at their finest to catch up financially.”

Nonetheless, it’s no shock that Jones’s household, the Handys, left behind the expanse of acreage to which they owed their preliminary successes. Whereas the Handys had a legacy value defending in Hazlehurst, shifting North or to extra city areas of the South throughout the Nice Migration typically meant higher job and academic alternatives, in addition to the hope of escaping racial violence, for a lot of Black rural households.

But the Handys, who had been hardly the one Southern Black landowners and farmers of that period, had been among the many few who managed to retain the rights to their land lengthy after spreading out throughout the nation.

Though tons of of 1000’s of Black folks acquired property within the many years instantly following the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation and the top of the Civil Warfare — although white folks had been typically unwilling to promote it to them at a good worth — that possession largely dwindled over the following century. Discriminatory lending practices minimize Black farmers off from capital, which contributed to foreclosures and tax gross sales; folks involuntarily misplaced inherited property by means of partition gross sales and clouded titles, typically stemming from the shortage of entry to property planning that made Black households so weak; the federal government seized property through eminent area; and a few Black households had been compelled to desert property within the face of violence and intimidation.

In 1910, Black folks operated and owned greater than 2.2 million acres of farmland in Mississippi, in keeping with authorities knowledge — nonetheless a sliver of the 18.6 million acres farmed by house owners, managers and tenant farmers statewide. By 2017, although, fewer than 400,000 acres of the 10.4 million acres of farmland within the state had been owned by Black farmers.

Altogether, between 1920 and 1997, Black farmers within the U.S. misplaced virtually all their land, value roughly $326 billion in immediately’s {dollars} by one estimate.

“‘That is an instance of what would have occurred if we had acquired our 40 acres from the start. We acquired it. Look what has occurred to our household on account of landownership.’”

“As a Black individual, so many people are so disconnected from our household, the place we come from — our roots — due to slavery, due to the Nice Migration, due to violence, due to folks being shot, and killed, and murdered,” Jones mentioned. “To be a Black individual in 2023, to have the ability to return to this land, and be like, ‘There’s 400 acres of land over right here that I come from, that I do know my historical past of, that I do know my roots, that I’ve cousins I can discuss to and might inform me tales’ — that’s unimaginable. It provides me such a way of delight and grounding and energy. I really feel highly effective.”

Because the federal authorities weighs potential pathways towards addressing a large and protracted racial wealth hole — H.R. 40, the Home invoice to review reparations that’s been repeatedly reintroduced, will get its identify from the 40-acre promise — Jones and her relations need policymakers to think about what Black households just like the Handys gained largely by gaining access to property, and the flexibility to take care of it immediately.

Tisch Jones on the land in Hazlehurst.

Patrice E. Jones

“We now have a complete historical past of ministers, lecturers, artists, entrepreneurs,” mentioned Tisch Jones, Jones’s mom, a professor emerita within the College of Iowa’s Theatre Arts Division and a civil-rights activist. “This land allowed that to occur, which is why I battle for reparations a lot. That is an instance of what would have occurred if we had acquired our 40 acres from the start. We acquired it. Look what has occurred to our household on account of landownership.”

‘I owe my life to this land’

Jones started to have vivid goals of the Hazlehurst land proper earlier than the pandemic’s onset, and began frequently driving the 2 hours from her New Orleans house to the household property because the U.S. financial system shut down. The land’s peacefulness and forests, accompanied by the 4 homes her ancestors constructed, drew her in, and he or she was enticed by the concept of rising her personal meals. However the property had been vacant for years, and the properties had been falling aside.

Nonetheless, “I fell in love,” Jones mentioned. “I spotted if I didn’t do one thing, no one would. I simply type of felt prefer it was my calling.”

“‘Patrice is a steward of the land, and he or she desires to make use of that land to present others the imaginative and prescient of being stewards of their very own.’”

Later in 2020, a white Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd, a Black man, spurring dialogue about reparations and racial fairness throughout the nation. Jones’s household’s ancestral land felt essential to a higher understanding of what Black folks had been owed, and her mom made the transfer from Minneapolis all the way down to New Orleans to assist see Jones’s work by means of.

“As a toddler, I didn’t perceive the significance of the land,” Tisch Jones mentioned. “I didn’t understand till I bought to be older and began studying extra about my historical past, and the historical past of my most direct household … what a gorgeous present we had.”

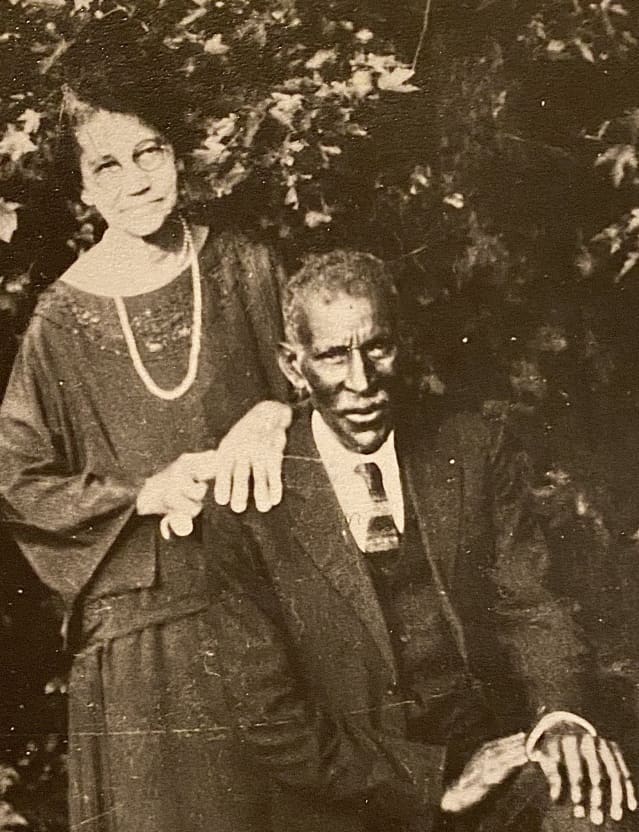

Patrice Jones’s great-grandfather, Rev. William Talbot Helpful, had documented the land’s historical past in an autobiography, and he or she has recognized virtually her total life that the land, her lineage and her lighter pores and skin had been the byproduct of each slave-owning and enslaved ancestors: Jones’s great-great-grandmother and Rev. William Talbot Helpful’s mom, Florence Geneva Helpful, was born to an enslaved girl and the son of the person who owned her, Mississippi Supreme Courtroom Justice Ephraim Peyton Sr., Jones mentioned. Florence’s father, a white man, helped her buy the property after she married the Helpful household’s namesake, Emanuel Helpful Jr., at 19.

Florence and Emanuel Helpful Jr.

Patrice E. Jones

However Jones has additionally recognized that with the assistance of that land, her ancestors had been capable of have safety that different Black households weren’t allowed.

The reverend’s spouse, Dorothy Pauline Nice Helpful, maybe additional recognizing the significance of what her household had created, additionally arrange a belief within the Nineteen Seventies to assist preserve the land’s repairs. The belief was ultimately handed down by means of generations of ladies within the household; in 2020, Jones endeavored to grow to be a trustee, a task she now shares with two different relations. (The title for the land itself is just not in that belief however, importantly, is just not in dispute both.)

Since then, she has been engaged on a revival of kinds, beginning along with her great-grandparents’ home, the biggest of 4 buildings on the property and the place the reverend and his spouse had meant to retire previous to their deaths. To this point, that’s meant gutting and releveling the house, whereas additionally including a brand new roof, new electrical energy, a brand new HVAC system and new drywall.

The opposite craftsman-style properties, constructed within the early 1900s and described by Jones as “teeny,” had been utilized by three of her great-uncles, who remained on the land and farmed till the mid-’80s, when the ultimate son of Florence Geneva Helpful and Emanuel Helpful Jr. died.

“They’re not falling — but,” Jones mentioned of the properties. “I’ve been doing the whole lot I can to mothball them.”

All of the whereas, she has documented the restoration course of on TikTok and Instagram

META,

garnering thousands and thousands of views on movies showcasing the property’s historical past, in addition to her pleasure related to it. In lots of the clips, she’s dancing. Typically she breaks down her household’s ancestry, too, drawing upon scores of audio information, pictures, newspaper clippings and authorities information to share enjoyable information — “My great-grandfather was a minister, and in 1932, Albert Einstein visited his church,” she says in a single TikTok — in addition to somber ones, like how her great-great-grandmother was listed as her personal white father’s “servant” on the 1880 census.

“I owe my life to this land,” Jones says in a single July 2021 TikTok video submit with 3 million views. “Black land issues.”

A number of the feedback on her movies reward the great thing about generational wealth in Black households, or say they hope to perform the identical type of revival with their very own household’s property.

Nonetheless, restoring the properties is a troublesome and costly endeavor: Jones arrange a GoFundMe marketing campaign in early 2022 to boost $60,000, however has raised solely 1 / 4 of that purpose. Adrienne E. Mason, a member of the family whom Jones described as “my fairy godmother,” additionally supported the mission, contributing about $60,000 in belongings, funds and a gazebo earlier than her dying in February. Mason, who was older and Black, had misplaced the household farm the place she grew up and located Black landownership immensely vital, along with caring for the humanities, Jones mentioned.

Jones has additionally tapped her private financial savings and cash left within the belief by her great-grandmother, which collectively totaled roughly $60,000.

Jones’s brother, Patrick Rhone, a 55-year-old author based mostly in St. Paul, Minn., has expertise restoring properties — he owns 4 properties together with his spouse — and is aware of what Jones is in for. However her work is nicely value it to protect the tales the household wish to inform future generations, he mentioned.

“This isn’t about possession; that is about stewardship,” Rhone mentioned. “Patrice is a steward of the land, and he or she desires to make use of that land to present others the imaginative and prescient of being stewards of their very own.”

Jones hopes to ultimately flip your entire property right into a therapeutic house for artists and writers of colour who want a spot to work, relaxation and join with their very own histories and relationships to land. Jones’s great-grandparents’ house could be the retreat’s predominant workplace, kitchen and gathering house, Jones mentioned, whereas she would break up time between New Orleans and Hazlehurst.

“I imagine all Black folks want land entry, as a result of we labored the land on this nation and constructed the financial system we’ve got immediately,” Jones mentioned. “We’d like this house. We’d like the house to relaxation, we’d like the house to develop, we’d like the place to study. We’d like a protected house.”

A time of peak Black landownership, and racial terror

Jones’s ancestors tended to the land in Hazlehurst throughout what wound up being a banner time for Black landownership within the U.S., although a promise to present property to previously enslaved folks went unfulfilled.

Because the Civil Warfare drew to a detailed in 1865, Union Basic William T. Sherman and Secretary of Warfare Edwin M. Stanton met with Black religion leaders and previously enslaved folks in Savannah, Ga., to debate what newly freed enslaved folks wanted to be self-reliant. At that assembly, Rev. Garrison Frazier, an ordained Baptist minister who had bought freedom for himself and his spouse solely eight years earlier than the gathering, made the case for landownership, in keeping with transcripts.

For a quick time, it seemed like Frazier might get his want. Days after the Savannah gathering, Sherman issued Particular Subject Order No. 15, which declared that 400,000 acres could be redistributed from Accomplice landowners to previously enslaved Black folks at 40 acres every.

Whether or not that possession could be unique, earned over time or merely momentary was unclear, mentioned Thomas W. Mitchell, a professor and director for the Initiative on Land, Housing and Property Rights at Boston Faculty Legislation Faculty. However it was nonetheless seen as a agency promise by not too long ago freed enslaved folks, who weren’t deterred from landownership even after then-president Andrew Johnson reneged on the short-lived dedication to 40 acres.

Black Individuals took on a number of jobs, pooled sources, requested the flexibility to buy land from their former enslavers, and resisted eviction from occupied lands till that they had acquired some 16 million acres of farmland by 1910, solely 50 years after the top of the Civil Warfare and the demise of reparations.

Associated: Black farmers misplaced $326 billion in land over eight many years. Stalled debt reduction may imply the ‘subsequent wave’ of losses.

“We had been nonetheless dwelling in a society, definitely within the South, the place its major financial engine was agriculture,” Mitchell mentioned. “In the event you had been going to have any likelihood to have any type of improvement socially and economically in our nation, it was virtually a prerequisite that you simply grow to be a landowner — and within the South, a landowner of farmland.”

One of many newly minted Black landowners was Jones’s great-great-grandmother, Florence Geneva Helpful, who was acknowledged because the baby of her white father, Ephraim Peyton Jr., and raised partially in his house. Her mom and grandmother, whom Peyton Jr.’s father as soon as enslaved, continued to work for the household after emancipation, Jones mentioned.

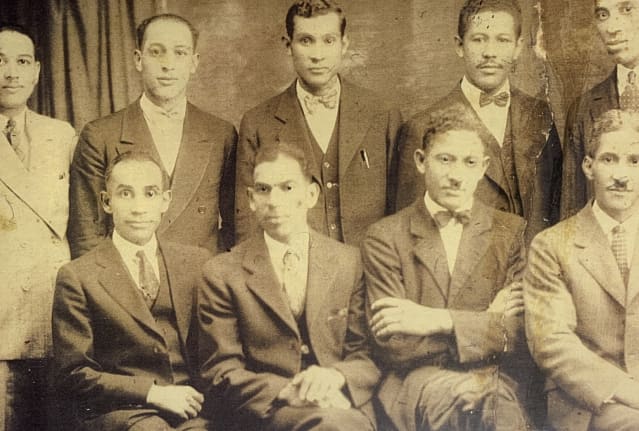

After Helpful married Emanuel Helpful Jr., she acquired her father’s assist in shopping for 40 acres of land. It’s unclear whether or not the quantity of acreage was intentional; Jones believes that as a result of the sale nonetheless occurred within the Reconstruction period, Florence and Emanuel might have looked for that measurement based mostly on the preliminary promise of 40 acres to freed enslaved folks. Both manner, the couple grew the property to 116 acres in time and raised 9 sons and two daughters there, utilizing cash from their crops to make sure every of their youngsters had a trade-school schooling or school diploma.

The Helpful brothers.

Patrice E. Jones

“By the top of this, we had a mortician; we had a minister, who’s my great-grandfather; we had Uncle Lon, who constructed the homes; we had a plumber, that was Uncle Dewey; the 2 ladies turned lecturers, so we had anyone who may educate folks,” Jones mentioned. “Then they married individuals who may carry one thing again to the land — Uncle Lon married Aunt T.J., who was a midwife, so we may now beginning infants.”

That was across the peak of Black landownership within the U.S., and a time by which the white-Black wealth hole was really narrowing. The white-to-Black per-capita wealth ratio was 56 to 1 in 1860 and ultimately declined to 9 to 1 in 1930, earlier than the hole finally stagnated and even widened after the Nineteen Eighties, in keeping with a 2022 paper by Ellora Derenoncourt at Princeton College and the College of Bonn’s Chi Hyun Kim, Moritz Kuhn and Moritz Schularick.

It was additionally a interval marked by racial terror, Mitchell mentioned, as Black landowners had been focused for white violence. For instance, Anthony Crawford, a Black farmer who owned 427 acres of land, was crushed, stabbed, shot and hung by white folks in Abbeville, S.C., in 1916 after an alleged dispute with a white service provider over the worth of cottonseed, in keeping with the Equal Justice Initiative, which has documented 1000’s of lynchings.

“You had plenty of households who, only for fundamental survival, uprooted and left oftentimes a profitable farm operation — as a result of the extra profitable it was, the extra they had been within the crosshairs,” Mitchell mentioned. “They mainly deserted their properties for self-preservation.”

Finally, all however 4 of the 11 Helpful youngsters left Hazlehurst, Jones mentioned, relocating to Chicago or different elements of the nation. However they at all times knew the land was there for them in the event that they wanted it.

“‘Loads of households lose that connection, lose that historical past, lose that legacy once they lose the land — as a result of we all know that land has worth, and so they’re not making any extra land.’”

The truth that the household was capable of maintain on to the property whereas many different members relocated was a “miracle,” thanks largely to the belief established by Jones’s great-grandmother Dorothy, Jones mentioned.

“She was savvy with cash,” Jones mentioned of Dorothy. “She purchased these certificates of deposit so a few years in the past, and so they wound up being some $30,000 whole by the point I cashed them out. An unimaginable girl; one in every of my best inspirations and idols.”

Black-owned property within the South is commonly not protected by a will or one other authorized instrument, so when an proprietor dies, the land is handed down informally to following generations with out a clear title, and possession turns into unstable; such household land, often called heirs’ property, has grow to be a key driver of Black land loss. Actual-estate speculators can “decide off one member of the family, after which go to the native courthouse, file a lawsuit, and ask for the compelled sale of your entire property,” mentioned Mitchell.

“One of many racial gaps on this nation that’s least well-known, however not shocking when you consider it, is that there’s a large racial estate-planning hole,” Mitchell mentioned.

Traditionally, many Black farming households have been skeptical of the authorized system as a result of it’s so hardly ever served them, mentioned Andrea’ Barnes, the director of the Heirs’ Property Marketing campaign on the Mississippi Middle for Justice, which offers households within the state authorized help to allow them to preserve, defend and make the most of ancestral land. In addition they typically lacked cash to pay an lawyer to arrange their property, or entry to an lawyer prepared to work with Black folks.

“When folks aren’t capable of maintain on to the land and use the land, they lose the flexibility to have an financial profit,” Barnes mentioned, whether or not that be by means of farming the property, leasing it, promoting off timber rights or profiting in different methods. “With heirs’ property, it’s weak.”

Barnes recalled that even her grandfather, a farmer who died in 2019 at 91 years outdated, noticed landownership as a method to finish intergenerational poverty. It was a degree of delight to depart that property behind for his household. However he was skeptical of property planning, whilst his granddaughter turned an lawyer.

Whereas Barnes wasn’t capable of persuade him to determine a will, he did partition the property so it might be handed all the way down to his youngsters, alongside together with his legacy.

“He was very vocal in regards to the significance of land and sustaining that land within the household,” Barnes mentioned. “Loads of households lose that connection, lose that historical past, lose that legacy once they lose the land — as a result of we all know that land has worth, and so they’re not making any extra land.”

‘We’ve bought one thing that’s ours’

Because the already-small inhabitants of Black landowners declines additional, there are fewer of them to share their tales of success, and fewer examples of what generations of property possession would have meant to marginalized households. Jones believes that Helpful Heights is a part of the Black historical past that must be instructed for generations to come back.

There’s loads Jones says she nonetheless doesn’t know, like what it was like for her great-great-grandmother to be raised alongside the white household that enslaved her personal mom, and to depend on that household for assist securing her personal financial freedom. However she is aware of that property possession is valuable; stewarding the land has even allowed her the flexibility to satisfy relations in Hazlehurst she’d by no means gotten to know.

Her 74-year-old mom, Tisch Jones, is proud that her daughter is dedicated to sharing that legacy. She had herself as soon as hoped to protect the land and open it up as an area for the humanities, and mentioned it’s “very heartwarming” to see that dream continued.

“So long as that land is there, and all that forest behind the land, we’re extraordinarily wealthy,” Tisch Jones mentioned. “We’ve bought one thing that’s ours.”